Being Too Early is Being Wrong

Timing is everything.

I stumbled upon the documentary General Magic expecting another Silicon Valley success story. The story tells the exact opposite.

General Magic spun out of Apple in 1990 with an impressive roster: Marc Porat as founder, Andy Hertzfeld and Bill Atkinson from the original Macintosh team, plus future tech leaders like Tony Fadell (iPod/iPhone creator), Megan Smith (future Google VP and White House CTO), and Kevin Lynch (Apple Watch architect).

The documentary follows the team on their mission to create a “personal communicator”—essentially a smartphone with email, games, and emoji. In 1992.

“There will be smart phones, smart pagers, and maybe even things like intelligent watches, for all we know,” Porat states in 1994, predicting both iPhone and Apple Watch decades early.

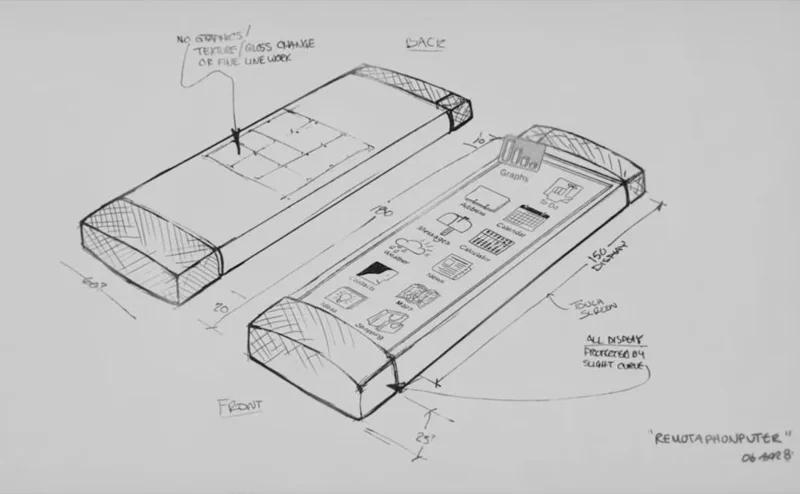

Archival footage shows concept drawings that look remarkably like today’s smartphones.

In the end, their device sells fewer than 3,000 units at $800 each, mostly to family and friends.

The product was simply too early.

The wireless networks were primitive and slow. The screen was small and hard to read. The supporting infrastructure was definitely not ready.

The documentary does a good job at showing just how much has to go into a product being successful.

Where the documentary fails is the narrative, that Porat suggests himself, that they had essentially created the smartphone—that they “had it."

Nope.

You just can’t take credit for inventing a product when the technology or society is not ready for it. They were too early, and being early is functionally identical to being wrong.

As journalist Kara Swisher puts it: inventing a smartphone in the 1990s was like inventing a television in the 1880s; there was nothing to show on it.

I learned this lesson the hard way.

In 2012, I joined Maluuba to build AI agents using natural language. We were early to the space—just us, Siri, and Google Assistant and only a handful of other small players. Our tech was legitimately impressive. We outperformed both Siri and Google on benchmarks, landed contracts with Samsung and BlackBerry, and pioneered interactions people use every day now. So much so we were awarded one of the earliest patents for conversational AI agents. We also nailed the startup theater: TechCrunch Disrupt, SXSW, slick launch videos. We were even the first to predict natural language would dominate IoT and smart homes use cases.

None of it mattered. Our technology was good—just not good enough. People expected natural language to handle infinite use cases, and our technology and product didn’t scale. The company ended up selling to Microsoft to build out their AI lab.

Now that ChatGPT has fulfilled the vision we saw coming, we can’t retroactively claim credit for seeing the future but failing to build it.

I’m not the only one with this story.

Clippy is another example. Microsoft’s Clippy, that office assistant from 1997. Steven Sinofsky, former Office team leader, explains in a recent article that Clippy’s value proposition was fundamentally correct—software should help you use software tools—but hit technological limitations.

Again, like Maluuba, ChatGPT and others have fulfilled Clippy’s vision—but only because the underlying technology finally caught up.

Sure, Clippy was a needed step along the way. As Sinofsky notes: “Clippy was a necessary failure—an early version of an AI assistant that hit a technological cul-de-sac but laid the groundwork for AI helpers” today.

Is the technology really here to make this thing useful? Practical? Affordable? Are societal norms going to allow for it? Is it good enough to bend those norms?

Ultimately, vision is nothing without the right timing.

The same applies to design and interactions.

Timing isn’t only about whether technology or users are ready—it’s about how long it will take them to actually adopt something new.

Take the Palm Pre. It introduced many gestures we use on our smartphones today, including swiping up from the bottom of the screen to close an app and go home. But was the Palm Pre really ready for mass adoption? Not everyone was ready to learn all these new interactions all at once.

Apple was smarter about timing. When they finally added a similar swipe-up to go home gesture, it had already been a decade since users were using touch gestures. Even then, they forced users to learn the new gesture by physically removing the home button from the iPhone. Users had no choice but to learn the new way. They timed the change of the entire physical form factor of the device to match the introduction of the new interaction.

And remember, the iPhone wasn’t the first smartphone. Amazon wasn’t the first online bookstore. Google wasn’t the first search engine. Facebook wasn’t the first social network.

I’ve changed how I think about building products entirely.

I’ve stopped romanticizing “visionary” ideas that failed. We celebrate being “ahead of our time” when we should be asking harder questions: Is this the right time, or are we building expensive monuments to our own cleverness? Do we really want to be the one building the neccessary failure for some other product’s success?

Now I ask one brutal question before building anything: Is the world actually ready for this, or am I just early enough to be wrong?